Our intimate relationships can offer a great deal of fulfillment; however, when the worry of infidelity becomes circular and persistent, it slowly chips away at trust. It is exhausting to find yourself in this cycle despite knowing it’s unlikely your partner is cheating. One part of you wants to know for sure, while the other part is tired of this pursuit and wants to trust. Along with worry, racing thoughts, and anxiety, it’s common to experience anger, guilt, shame, and confusion.

If you’re caught in this cycle, you’re not going “crazy” or “losing your mind,” even though it may feel like it. You’re experiencing infidelity anxiety, and it’s very common. Luckily, science and the field of psychology have uncovered valuable insights into anxiety, and there’s a lot you can do to overcome it.

In this article, I’ll explore why you may be experiencing these persistent worries and provide practical strategies to help you respond to anxiety in new ways that help decrease it long term.

Before jumping into strategies, it’s important to understand some key concepts.

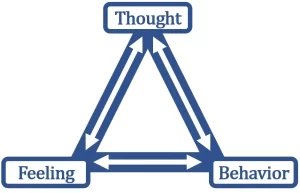

Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

Our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors all influence one another. For example, if you think, “What if my partner is cheating?” you may feel anxious and have an urge (behavior) to ask your partner for reassurance. Think of it like the triangle below.

When you’re emotionally triggered, it’s common for feelings, thoughts, and actions to blend into one. When this happens, you enter into autopilot mode, and emotions take complete control. Without realizing it, in an instant, you can jump from thinking, “What if she’s cheating?” to impulsively acting in a way that isn’t in line with your values: Blaming your partner, prying into social media accounts, or excessively asking for reassurance.

It is difficult to separate feelings from emotions from urges when you’re emotionally triggered. They become one, and you lose control.

Many of the strategies I’ll introduce aim to increase your awareness of all three parts of the triangle. When you can identify and label each part, you turn off autopilot and gain more control.

Let’s focus on thoughts and feelings more by exploring anxiety and worry.

Defining anxiety and worry

Anxiety and worry often get used interchangeably. But they’re different.

Worry is a cognitive process. It’s a process of mentally engaging with thoughts about future undesirable events. You can think of worry as a two-step process:

- An automatic worry thought appears

- You engage with the thought

For example, imagine watching a movie that involves infidelity in the storyline, and an automatic thought appears: “What if my partner did that?”

This isn’t necessarily a worry just yet.

Worry occurs when we engage and put energy into this automatic thought, for example:

- Automatic thought: “What if my partner did that?”

- Mental engagement (worry): “Well, I did notice him acting a little off yesterday.”

- Mental engagement (worry): “What if I’m so blind to the warning signs? I’ll be caught off guard.”

- Mental engagement (worry): “Everything we’ve built together would be a big lie and fall apart.”

Worrying is a choice, but often you don’t realize it because the automatic thought is so good at convincing you there is a real danger when there isn’t any danger. As a result, it feels reckless, even dangerous, to refrain from engaging with the automatic thought.

Other important points:

- Automatic thoughts are not within your control. Engaging with the automatic thought is.

- Some of us are more susceptible to worrying due to genetics, past experiences, alcohol and drug use, and mental habits.

I’ll talk more about what you can do about worry but let’s first explore the feeling that often accompanies worry: anxiety.

Anxiety is a feeling in our bodies. It’s what we feel when we get stuck in circular worry. We feel anxiety in all sorts of different ways. Here are just a few examples:

- Racing heart

- Heart palpitations

- Lump in the throat

- Restless

- Stomachaches

Anxiety can hit at any time. It can indicate a real threat, but most often, it’s a false alarm. That is to say, anxiety, more times than not, misleads us.

The challenge with anxiety is that a false alarm and a truly dangerous situation feel the same. It’s impossible to distinguish the two from one another. This is why it’s so difficult to avoid acting on the urges when you’re anxious about your partner cheating, even though you logically know the probability of your partner cheating is low.

Why would our brains mislead us?

The Brain

Our brain’s threat detection system keeps us alive and is highly effective at doing just that. The only thing is, it’s terrible with accuracy and is constantly overreacting to situations. It works off the premise, “I don’t care about being right. I want to keep you alive. We’ll figure out the details later.”

For example, you’re walking down the hall in your house, and a family member unexpectedly jumps out of a room. Before you’re consciously aware of what’s happening, your threat detection system kicks in, takes complete control, and forces you to jump back, increases your heart rate, and you scream. It all happens outside of your control.

This is your threat detection system; even though it’s overreacting, it works properly. It’s made to overreact. Another name for this is the “fight or flight” response.

The tricky part about the threat detection system is that it doesn’t understand logic or language. So, even though you know that you’re perfectly safe, and no matter how much you try to convince your “fight or flight” response that it doesn’t need to react in certain situations, it won’t understand.

This is why it’s common for people who experience anxiety to feel like “I’m going crazy” or “I think my brain is broken.” They know there is nothing threatening, yet their brain is screaming, “Danger!”

Now that you understand your brain’s threat detection system, let’s turn our attention to the overall goal of dealing with infidelity anxiety.

Finding This Helpful So Far?

Subscribe to Weekly Thoughts on Anxiety + Events

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

The Goal

Anxiety and worry are incredibly uncomfortable, so it’s tempting to have the goal of getting rid of them entirely. Though it’s a nice fantasy to imagine a life free of worry and anxiety, they serve an essential function: Protection.

Worry and anxiety about cheating are not always bad. If there is clear evidence of infidelity, these processes serve as signals to take protective action. When we are in harm’s way, we want our brain’s threat detection system to activate and urge us to act in a manner that keeps us physically and emotionally safe.

Because worry and anxiety protect us, it’s not wise to eliminate them. We would be left extremely vulnerable to being harmed. Instead, our goal should be to acknowledge and allow these emotions to be present. At the same time, we assess and determine whether they are guiding us in a helpful or unhelpful direction.

Anxiety is like a small child; it gets our attention when something important happens. At the same time, it constantly overreacts, screaming and yelling when there is no danger.

Even though a child constantly overreacts, we never want to put ourselves in a situation where we can’t hear his cries. If we do, eventually, he will get hurt or even worse.

Instead, your job is to be the parent of the child. You want to respond to his cries but don’t want to rush him to the hospital every time he screams. This approach allows you to benefit from the cries’ protective function while guarding against overreactions.

One way to help find this balance is to understand what triggers your anxiety about cheating. And to understand the anxiety cycle.

Triggers and the anxiety cycle

By understanding what triggers our anxiety, we can better prepare for the overreactions.

We all have things that trigger worry and anxiety. Some originate outside of us, while others come from within.

External events that cause worry about cheating:

An external event happens to us and originates outside of us. It could be the action (or inaction) of a person, or it could be something that happens in our environment:

- Your partner doesn’t respond to texts, emails, or calls.

- You notice a change in your partner’s demeanor.

- You see your partner guarding their cell phone or computer activity.

- A friend discloses that they found out their partner cheated on them.

Internal events that cause worry about cheating:

Internal events originate within us:

- A random image of your partner cheating pops into your mind

- A worst-case scenario entering your mind

- Replaying and analyzing a recent interaction

- A “what if” thought

The anxiety cycle

You can think of anxiety, and its maintenance, as a step-by-step process:

- Triggering event (external, internal, or a combination).

- The feeling of anxiety hits (i.e., racing heart, stomachaches, etc.).

- Urge to avoid or protect yourself against the “danger.”

- Anxiety decreases in the short term.

- Long-term maintenance of the anxiety.

Why does decreasing anxiety in the short-term reinforce it long-term?

Let’s go back to the threat detection system.

Remember, it doesn’t understand language; instead, it speaks the language of experience. It watches how you react when it sends you danger signals. Suppose you respond in ways consistent with danger (e.g., checking your partner’s text messages, asking for reassurance, blaming your partner for your feelings). In that case, you teach the threat detection system that it’s accurate in the particular situation, unintentionally telling it, “Great job! You’re right about this being a danger. Continue sending me the same signals in the future.”

You can think of a triggering event, external or internal, as a spark. Then, the initial and instantaneous feelings of anxiety as a small flame. Next, avoidance or protection is the fuel. When we take avoidant or protective action, it’s pouring gasoline on the flame of anxiety. The result is a raging, persistent fire.

What parts of the anxiety cycle do we have control over?

Things we DON’T have control over

- Anxiety triggers – We might be able to reduce triggers in certain situations. However, ultimately, we don’t choose whether or not something triggers our threat detection system.

- Automatic thoughts – Automatic thoughts are just that, automatic and outside of our control.

- Partner’s behaviors – Even though anxiety may urge you to focus on your partner’s behaviors, ultimately, you can’t change your partner.

- Feelings – None of us choose how we feel. If you did, you wouldn’t need to read this article; you’d simply choose to feel a different way.

Things we DO have control over

- Our reaction to anxiety – Considering everything, all we have control over is anxiety’s fuel: Choosing whether or not to engage in avoidant/protective behaviors or with worry thoughts when anxiety hits.

Focusing on what you have control over

So often, when anxiety strikes, it’s a false alarm, and our focus is on trying to change or control the things we don’t have any control over.

One of the best things you can do when feeling anxious about infidelity is to remind yourself what you have control over and focus your energy there. This is easier said than done, but with repetition and practice, this process will become more automatic, and it will be easier to resist the urges of anxiety.

Let’s look a little closer at the thing you have control over: Your reaction to anxiety.

Your reaction to anxiety

Avoidant and protective behaviors are effective in the face of actual danger, but if it’s a false alarm, engaging in these behaviors only reinforces and intensifies the anxiety, perpetuating the cycle of anxiety.

Let’s explore some common behaviors that anxiety often urges someone to engage in when dealing with infidelity anxiety:

- Withdrawing emotionally and avoiding your partner

- Seeking excessive reassurance from your partner

- Avoiding discussing your fear of infidelity with your partner or others

- Overanalyzing your partner’s behaviors.

- Constantly monitoring your partner’s activities.

- Attempting to control or restrict your partner’s actions.

- Constantly comparing yourself to others.

- Turning to alcohol or drugs to numb the anxiety.

- Excessively researching articles on the Internet reading about signs of cheating.

If it’s a false alarm, this is a list of protective behaviors you should probably avoid if you want to step out of the cycle of anxiety.

It’s a paradox: When faced with a false alarm, seeking “safety” only serves to maintain the cycle, while accepting, embracing, and even welcoming the “danger” can help break free from it.

It is easier said than done because false alarms feel indistinguishable from real danger. The physical sensations are identical. Stepping outside the anxiety cycle requires going against our instincts by confronting the feeling of danger, going one step further, and even welcoming it.

Let’s go back to the brain to understand how it learns.

Teaching your brain a new lesson

Remember, your brain’s threat detection system:

- Reacts instantaneous, but at the cost of accuracy.

- It values your life over accuracy. It’s built to overreact.

- It doesn’t learn through language or logic.

- A false alarm feels the same as an actual danger.

Ultimately, you can’t control if or how your threat detection system reacts in any given situation. However, there are things you can do to teach it new lessons and increase the chances that it will respond differently in the future.

Imagine going to a haunted house at a Halloween carnival. Before entering, a carnival worker pulls you aside and gives you an hour PowerPoint presentation on how safe the haunted house is: “We’ve been in business for 30 years, and not one person has ever been injured. Not even a stubbed toe!” The carnival worker intends to comfort you, hoping your “fight or flight” response won’t be triggered. However, no matter how convincing the presentation is, your “fight or flight” response will get triggered at some point inside the haunted house. Why? The threat detection system doesn’t understand language. Instead, it speaks the language of experience.

If you say to yourself, “I’m not going back in there. That was too scary,” and avoid the haunted house, you reinforce the anxiety long-term. Why? Remember, your brain is watching how you react.

The threat detection system sends danger signals and observes how you respond. Suppose you respond in a way consistent with danger (like avoiding the situation). In that case, you’re teaching your brain through your actions, “The signals you sent me were accurate. I was in danger. Keep sending me the same signals in these types of situations.”

If you want to teach your brain not to react, you do the opposite: you go back inside the haunted house.

When you go back in again, your threat detection system will likely send you the same signals (and maybe even more intense signals), but it’s watching how you react. As you walk back inside the haunted house, while your brain screams, “Don’t!” you’re teaching it a new lesson. You’re saying, through your actions: “You’re wrong about this. This is a perfectly safe situation, so I’m returning, regardless of what you tell me.”

Let’s go back to the example of anxiety being like a child.

Finding This Helpful So Far?

Subscribe to Weekly Thoughts on Anxiety + Events

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

The Child Brain, The Parent Brain, & The Grandparent Brain

In many ways, we have three brains:

The Child Brain – This is the threat detection system I’ve mentioned before: Highly reactive, automatic, not conscious, not logical, doesn’t learn through language. Only learns through experience. It’s perfect for keeping us safe and alive. However, it constantly overreacts. It’s wrong most of the time. At the same time, we’re lucky to have the Child Brain because it’s better to have a system that overreacts to possible threats than one that underreacts or doesn’t react.

The Parent Brain – intelligent, logical, aware, conscious, not automatic, learns through language. It’s the analytical system. Just like all parents, though, it’s not perfect. Often it wants to shelter the Child Brain by helping it avoid or escape “dangers.” It’s hard not to. Seeing the Child Brain crying and screaming pains and scares the Parent’s Brain. But, when it does give into the child’s false alarms, the Child Brain becomes even more sensitive to stressors and slowly starts to internalize unhelpful lessons: “If my parent is reacting like we’re in danger, this situation must be dangerous.”

The Grandparent Brain – wise, logical, and highly aware. It’s the highest system. This brain coaches the Parent Brain to understand that just because the Child Brain is screaming and crying doesn’t mean anyone is in danger. It’s uncomfortable but not dangerous. The Grandparent Brain teaches the Parent Brain to react in a way that teaches the Child Brain to cope with uncomfortable situations without needing to be sheltered. We don’t do this through language; the Child Brain is too young. The Child Brain only learns through experience. Only by repeatedly staying in “dangerous” situations, over and over, does the Child Brain learn that it can cope and that the situation isn’t dangerous.

How can you make it easier to access the Grandparent Brain? One of the best ways is to understand how the Parent Brain gets pulled into the drama of the Child Brain.

Confronting thoughts to gain courage

Again, the Parent Brain is smart but vulnerable to the Child Brain’s overreactions.

Its biggest vulnerability is through automatic thoughts. The Child Brain screams, and more times than not, the Parent Brain experiences an automatic worry, anxious thought: “We’re in danger.” These types of thoughts don’t reflect reality. They distort reality. In psychology, we call these Cognitive Distortions.

Here is a small sample of some Cognitive Distortions:

- Black & White Thinking: You may notice your brain tending to categorize your partner as completely trustworthy or entirely untrustworthy, disregarding the complexity and nuances involved. In reality, trustworthiness exists on a spectrum full of gray areas.

- Catastrophizing: Anxious thoughts can lead you to imagine worst-case scenarios regarding infidelity: “My partner is cheating, and it will destroy our relationship, leaving me alone and broken forever.” Catastrophic thoughts fuel anxiety.

- Personalization:Our minds can blame ourselves for our partner’s potential infidelity, even when the reasons lie outside our control. We might think, “If my partner is distant, it must be because I did something wrong,” ignoring other possible factors that could be influencing their behavior.

- Negative Filtering:You may notice your attention only focusing on the negative aspects of your relationship, disregarding positive or neutral experiences. You may fixate on a suspicious incident or mistake while dismissing all the relationship’s strengths.

- Mind Reading: In relationships, it’s common to convince yourself that you know what your partner is thinking, feeling, and their intentions based on their behavior or subtle cues. However, the reality is, none of us are mind readers.

- Emotional Reasoning: Emotions can deceive us into believing they reflect the truth. However, it’s important to remember that just because you fear your partner cheating doesn’t automatically make it true.

- Should Statements: Thoughts can impose unrealistic standards on ourselves. You might think, “I should never feel jealous or insecure,” without acknowledging that occasional doubts and anxious emotions are normal in relationships. Or thoughts may place unrealistic expectations on your partner, “She should know why I’m upset!”

- Overgeneralizing: Our brain tends to draw sweeping conclusions based on limited evidence. A simple, innocent situation can trigger us to believe, “If my partner doesn’t answer their phone immediately, it must be because they’re engaged in an affair.”

It is important to remember that we have no control over automatic distorted thoughts popping into our Parent Brain. Equally important is the understanding that distorted thoughts are completely normal and experienced by everyone.

Since we have no control over these thoughts, it’s clear we can’t prevent them, yet often we try to. A 2018 study on thought suppression and involuntary “mental time traveling” (reflecting on the past or envisioning the future) discovered that when individuals actively try to stop thoughts, those thoughts tend to resurface with greater frequency.

So, what do we do?

Most of the time, cognitive distortions are present, and we believe them to be true. As a result, they take us for a wild ride. This is an example of being caught up in the Parent and Child Brain.

The best thing we can do with distorted thoughts is identify and label them. Don’t try to stop them. Don’t try to control them. Just label them: “Oh, that’s a ‘Catastrophizing’ thought.” Labeling these thoughts means you’ve moved into the Grandparent Brain, the highest part of your brain.

Rumination and thoughts

We may not control our automatic worry thoughts or cognitive distortions, but do we have control once these thoughts appear? Yes, but not in the sense of trying to control or suppress our thoughts forcefully.

When I use the term “worry,” remember, as I mentioned earlier, this goes beyond simply having an automatic thought. It refers explicitly to active engagement with automatic thoughts. This process is also known as rumination.

Dr. Michael Greenberg, an expert in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, defines rumination as follows: It involves actively engaging in mental problem-solving, which includes activities like analyzing, mentally reviewing, checking, visualizing, monitoring, and focusing on the problem.

However, there is a crucial distinction between rumination and actual problem-solving. Genuine problem-solving leads to a resolution, after which the thought process stops. In contrast, rumination creates the illusion of problem-solving; it’s circular, where you repeatedly replay the issue in your mind without reaching any meaningful resolution.

When you worry about your partner cheating without any evidence or reasonable suspicion, you’re likely engaging in what appears to be productive and something that is keeping you safe, but it is essentially unproductive busy work.

One primary reason this worry is unproductive is that your brain fixates on a question that is impossible to answer. It’s impossible to achieve 100% certainty about whether your partner is cheating.

Let’s talk about uncertainty.

Reassurance seeking and uncertainty

“But, I could ask my partner. I could ask to see their cell phone and email messages. These are ways I could be 100% certain.”

Logically, seeking outside reassurance makes perfect sense. In reality, though, reassurance is like a drug. We get it and find short-term relief, but then the worry and anxiety come back, often stronger. Then we need more and more reassurance to get the same level of relief as before.

If you focus on seeking reassurance from your partner, you’ll likely be spinning your wheels. The solution isn’t outside of you; it’s within you. It’s how you respond to those automatic worries that matter.

Another helpful way to understand reassurance seeking is by acknowledging what it’s after: Absolute certainty.

Achieving 100% certainty is tempting, as it promises anxiety relief. However, achieving 100% certainty is impossible.

Consider this: How can you be sure your partner is NOT cheating or will NEVER cheat? While there are ways to establish 100% certainty if your partner IS cheating, the reverse is impossible. This lingering uncertainty, no matter how small, is where anxiety finds an opening. And if your focus remains on obtaining 100% certainty, you open the door for anxiety.

Once again, here is the paradox of anxiety: The more we try to obtain certainty, which feels safe and appealing, the more fearful and anxious we become. As we start to embrace and welcome the uncertainty, we experience less anxiety.

One way to view anxiety is to consider it an intolerance for uncertainty. It’s like having an allergy to uncertainty.

Instead of trying to obtain the impossible (certainty), one goal you might consider experimenting with is to increase your tolerance for uncertainty. Just like building muscles, this process takes time, consistency, and deliberate practice.

One effective strategy for increasing your tolerance is to become aware of your urge to seek reassurance and consciously resist giving in to it. Instead, label the urge and recognize where it will lead: “I’m experiencing an urge to seek reassurance. I’m trying to achieve the impossible: certainty. I know where this will lead, though: More anxiety and more reassurance seeking.”

By labeling your self-talk and urges, you shift away from the Child and Parent Brains, where anxious impulses take control, to the Grandparent Brain, where you can exercise control over impulses.

Observe and don’t engage

We’ve established that you can’t stop the worry thoughts. If you try, it will just make it worse.

We’ve also established that seeking external reassurance will also make it worse.

The only other choice is to accept the junk that pops into your mind and consciously choose not to engage with it.

And engaging with your thoughts looks like this:

- Trying to answer the question of whether your partner is cheating or not.

- Trying to stop the thoughts.

- Judging the thoughts, “I shouldn’t be worrying about this.”

- Trying to inject other thoughts into your head, but it keeps popping back.

Instead of these things, simply watch your thoughts like a passing weather system.

When it’s mostly sunny, this is easy. When there’s a hurricane, avoiding engaging with the thoughts will be more challenging as there will be more urgency to relieve the discomfort.

The more we notice, without engaging with our thoughts, the easier it becomes. We teach ourselves to be passive observers rather than an active participants in our worry thoughts.

Go to the worst place on purpose

Another exercise to do is to follow your worry to the worst-case scenario. It is a little uncomfortable or scary for some people. So, take your time.

- What if my partner is cheating? Then what?

- Well, then, it’s going to hurt bad. And if that happens, then what?

- Well, I don’t know if I can stay with this person. And if that happens, then what?

Keep asking yourself the “Then what?” question until you reach the bottom. What we usually find is that, sure, it’s something we want to avoid. But it’s also something we can survive.

Finding This Helpful So Far?

Subscribe to Weekly Thoughts on Anxiety + Events

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

Identify your core belief

After getting used to just watching our thoughts, it’s helpful to identify their source. All of us hold certain beliefs about ourselves. In psychology, we call these “Core Beliefs.” Core beliefs are narratives we tell ourselves about ourselves. Core beliefs are important because they drive our automatic thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Take this example situation of two different people going through the same event:

Event: John texts his girlfriend on a Friday night. He usually gets a response back instantly. It’s been over an hour, and he still hasn’t gotten a reply back:

|

PERSON |

CORE BELIEF |

REACTION |

|

A |

“I’m unlovable” |

Thought: “She’s probably with another guy” Feeling: Anxiety, panic Behavior: Text more, call several times |

|

B |

“I’m lovable” |

Thought: “I hope John’s ok” Feeling: Slightly disappointed Behavior: Makes plans with another friend |

And most of the time, this occurs outside our conscious awareness. In a sense, we lack control and are subject to the invisible forces of our core beliefs. Nevertheless, we can bring them into the light and regain control. One technique you can apply to yourself is called the downward arrow technique.

Start by identifying a situation and noting the automatic thought associated with it. For example, when you text a friend, and they never reply, the thought “They’re mad at me” may arise.

- Next, ask yourself, “What does that mean to me if it’s true?”

- “Well, it means that he doesn’t like me.”

- So, you continue probing, “What does that mean if it’s true?”

- “Well, it means that I’m not good enough.”

This way, you uncover a core belief: “I’m not good enough.”

Attachment theory

Again, it’s important to address our reaction to the worry first instead of trying to analyze our past and figure out the root cause. That’s the same as arriving at the scene of a car wreck. Instead of jumping to care for the victims, you investigate to figure out what happened and whose fault it is.

At the same time, looking at our past can be very helpful, and attachment theory is a great tool that gives us some context to our relational patterns.

Attachment theory, in psychology, says that our early relationships with our caregivers mold how we relate to others throughout the rest of our adult lives. We develop internal working models or templates of how relationships work. There are four attachment styles, but I will cover three:

- Secure attachment

- Anxious attachment

- Avoidant attachment

A person with a secure attachment style generally believes people will be there for them. Their relationships are generally consistent and balanced.

Individuals with an anxious attachment style experience constant worry about being abandoned by others. They often seek reassurance that others love and will be there for them.

A person with avoidant attachment believes others will not be there in times of need. There is distrust, high motivation to be independent, and a general avoidance of placing themselves in situations where they rely on others.

How is this relevant?

It can be helpful to consider which attachment style you might fit into. For instance, if you relate to the anxious attachment style, this information is valuable to carry with you. It can serve as a reminder that your brain tends to default to worrying or expecting that others will leave you, leading you to seek reassurance. Understanding this can empower you to challenge automatic worry thoughts and experiment with resisting the urge to seek reassurance.

By recognizing that attachment styles can evolve and change over time, we open ourselves up to the possibility of growth and transformation in our relationships. The good news is, just like core beliefs, attachment styles aren’t set in stone.

Conclusion

Addressing your fear of infidelity is brave work. It takes an incredible amount of courage to lean into the uncertainties of being in a relationship and avoid engaging in what the emotions urge us to do so strongly. With practice, repetition, self-compassion, and communication with your partner, it’s possible to teach the brain new lessons. As it learns new lessons, it develops new mental habits that become more automatic and dominant, and the old, less helpful habits start to die off.

I hope you found this article helpful. If you did, you might find my Self-Help section useful. You might also want to subscribe to my Weekly Thoughts on Anxiety.

References

Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775. Clark, G. I., Rock, A. J., Clark, L. H., & Murray‐lyon, K. (2020). Adult attachment, worry and reassurance seeking: Investigating the role of intolerance of uncertainty. Clinical Psychologist, 24(3), 294-305. doi:10.1111/cp.12218

Del Palacio-Gonzalez, A., & Berntsen, D. (2018). The tendency for experiencing involuntary future and past mental time travel is robustly related to thought suppression: An exploratory study. Psychological Research, 83(4), 788-804. doi:10.1007/s00426-018-1132-2

Greenberg, M. (2020, October 20). Defining rumination. Retrieved March 27, 2021, from https://drmichaeljgreenberg.com/defining-rumination/

Riaz, A., & Jamil, K. (2020, July). Love Can Only Make Things Work Out: CBT And Interpersonal Therapy Case Study. In Technium Conference (Vol. 5, pp. 18-07). Sally Planalp, James M. Honeycutt, Events that Increase Uncertainty in Personal Relationships, Human Communication Research, Volume 11, Issue 4, June 1985, Pages 593–604, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1985.tb00062.x